Today’s post is a personal one. But if you bear with me, you will see that it explores a recurring theme here – the central importance of associational life in local communities for the health of democracy in America. And it does so from a less familiar and thus potentially more illuminating vantage point.

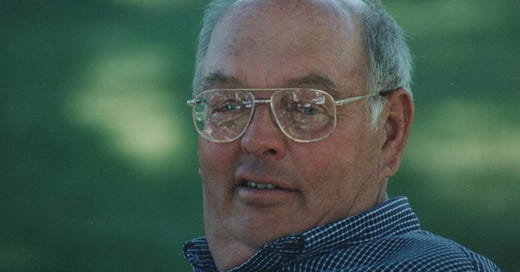

My father passed away four weeks ago. He died in the farmhouse where he had lived for most of his life, a few miles east of the town of Mason in Ingham County, Michigan. His own father had lived in that same farmhouse, and his grandfather before him.

One of Wendell Berry’s fictional characters, reflecting upon the death of an old farmer, observes that “it’s not a tragedy when a man dies at the end of his life.” Pete Stid certainly died at the end of his. He was 88, and his passing released him from the burden of an illness that had laid him low over the last couple of years.

Dad had a good run. He was called to farming and pursued his vocation for nearly 60 years, most of them alongside his brother and best friend, my Uncle Joe, who died back in 2007. The Stid brothers farmed hogs, corn, soybeans, and wheat, supporting two households with the fruits of their daily labor.

My father married my mother Sara, who survives him, in 1960. They raised a bustling family together – four sons, eleven grandchildren, and three great grandchildren. Like most families, we have had our share of sorrows and joys, but on balance, the latter outweigh the former.

As friends and neighbors came to visit us at his memorial service, we talked about Dad’s life as a farmer and his central place in our family. We also retold stories of his younger days – how as a boy his uncles gave him the job of leading a docile team of draft horses in haying season, or the mischief that he and Joe got into walking home from the one-room country school they attended through the eighth grade, before they went to high school in town.

In this newsletter, I want to recall Dad’s contributions as a fellow citizen and member of his community. Apart from four years studying agricultural economics at Michigan State University and his time in the Marine Corps, he lived and farmed in Mason throughout his life. He had an unspoken but abiding commitment to making the community of which he was a life-long member a better place. Not a superior or altruistic member, mind you – Pete Stid disliked pretension and could see it coming a mile away – rather, just someone who did his part.

“So, can we count on your vote for the millage?”

In the best American tradition, Pete Stid first decided to run for office because he was a fed-up taxpayer. In the late 1960’s, a field he and Joe worked sat next to the school district’s bus garage. It was a big field that took them a full week to plant. The first day, as he was getting started, Dad watched as a janitor from the school district office drove the superintendent’s car out to the garage and gave it a good wash. The car-washing ritual then repeated itself every afternoon at the same time, witnessed by an increasingly irate taxpayer riding back and forth on his tractor, shaking his damn head as he planted corn. By the week’s end, he had had enough. Encouraged by my mother, who told him if he was so upset by the car-washing he should do something about it, he decided to run for the school board and put a stop to it.

He won, and while he could not eliminate the superintendent’s perk entirely, he at least managed to change the frequency of the car wash from daily to weekly. Thus began his journey from firebrand to civic leader. Dad later recalled how shortly thereafter Monty Snow, an older farmer and board member from the west side of town, took him aside for some valuable counsel:

“[He] told me something I always remembered and tried to follow…most people who come on the board have an ax to grind. But if you keep your comments to a minimum and listen and observe for six months or a year, you will stand a much better chance of understanding what is going on and getting good things done for the schools.”1

Dad proceeded to do just that for 16 years, throughout the period my brothers and I attended Mason Public Schools. He became president of the board in 1975. His main goal in that role was keeping Glenn Doran – the highly capable superintendent the board had recently hired – on the job and freed up to do it well.

My most vivid memories of Dad’s service on the school board came from the part of the job he did from home. Whenever the school district needed to raise additional money for its budget, it had to propose an increase in the millage rate for property taxes, which the voters then had to approve. Dad’s job was to get his fellow farmers in the district to vote for the increase.

They were a tough crowd, frugal almost to a fault and skeptical (as he had once been) that the district needed additional money. Still, he had to hear them out and ask for their votes. So, after working all day in the fields, Dad would come in, eat supper, go to his office, and get on with his canvassing. I often pretended to read baseball box scores at the kitchen table so I could eavesdrop on his side of these conversations. For reasons I couldn’t really explain at the time, I found them fascinating.

Dad would always start by asking how his caller was doing, how much rain they had gotten recently, and whose crops were looking good on their side of town. Then he would circle around to the topic at hand – I expect you’ve heard, he would say, that we have a millage vote coming up. Judging by the silence that typically ensued, the person had indeed heard. Dad would listen to them. He might offer a correction to exaggerated notions of how much teachers got paid, or personally vouch for the fact that Glenn Doran was running a tight ship. But mostly, he listened.

Finally, at some point, he’d put the question out there: So, can we count on your vote for the millage? I couldn’t hear the answers, of course, but regardless, his response was always more or less the same. He’d say something along the lines of, fair enough, I appreciate that, thank you for hearing me out. His tone implied these were matters that reasonable people could disagree on and still be friends. So far as I could tell, he never chided those who said they were voting “no” nor flattered those who planned to vote “yes.” He let them get back to their evening, and he moved on to his next call.

Formal and informal volunteer roles

Dad volunteered for many years as a leader in the Skeeter Hill 4-H Club. It was under its auspices that my brothers and I showed our pigs each year at the Ingham County Fair. The fair had been the highlight of the summer for farm kids when Dad was growing up, and so it was in ours too. Thus every year in the first week of August, we’d reunite with our friends from 4-H and Future Farmers of America (FFA) clubs across the county at the fairgrounds in Mason.

In theory, we were all there to exhibit the livestock that we had carefully selected, spruced up, and trained in the run up to the fair. In practice, we also spent a lot of time drinking milkshakes, playing dodgy games overseen by barking carnies, and trying to sneak into the Ripley's Believe It Or Not! tent. At night, we watched tractor pulls and demolition derbies from the grandstands. So long as we fed and watered the animals we were responsible for and kept their pens clean, Dad did not mind us having fun.

At the fair, Dad helped run the hog show and barn with Mike O’Malley, a gentle giant who taught vocational agriculture and led the FFA chapter at Mason High School, and Bill Wheeler, who did the same in Webberville. They joined with their counterparts from the cattle and sheep barns to orchestrate the livestock auction, where local merchants bid on and bought the several hundred hogs, steers, lambs, and goats that club members exhibited at the fair. This same crew of club leaders then spearheaded the load out that emptied the barns of all the livestock the first morning after the fair ended. Dad worked incredibly hard the entire week to make sure everything ran smoothly. By the end of every fair, he was even more worn out than my brothers and me.

Looking back, I realize that the Stid brothers operated an informal workforce development program on their farm. Before my brothers, my cousin and I were old enough to work in earnest, and then after we left home, my father and uncle hired men to help them out. The work didn't pay much and was as hard as it was relentless – baling straw, castrating hogs, pitching manure, picking stones, etc. The young men who took the job did not have many other options. So each morning they'd rumble out to the farm, park their motorcycles and muscle cars beneath the shade of our oak tree, and get to work.

My father and uncle did not concern themselves with what these men had done or failed to do before they hired them, nor how long they wore their hair (a liberal policy back in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s). Indeed, they appreciated that the biggest rowdies often stood out as the best workers. The typical pattern was for these men to work for us over a couple of years, then – backed by a strong reference from the Stid brothers – find better paying work on a GM assembly line up in Lansing, with a local construction crew, or as a plumber's apprentice. Talking with several of these men when they turned up decades later at my uncle's funeral, and more recently at my father’s service, they expressed gratitude for the leg up they had gotten from Pete and Joe Stid all those years ago.

Dad also provided informal eldercare, looking after several widows who lived alone in drafty farmhouses alongside fields that he and Joe rented from them. Whenever we had a cold snap or ice storm in the winter, Dad would take one or two of his sons along as he checked in on Marion Dowling, Pearl Aseltine, and Eural Royston. We’d take a spade to scrape the ice and snow off their back steps while Dad sat and visited with them in their kitchens. The ancient Mrs. Royston heated her house by means of an old-school iron stove that she also used for cooking. We’d bring in and stack firewood for it, then sit next to her and Dad by the stove to get warm, our mouths agape at the clowder of cats roaming around her kitchen like lions on the savannah.

Later on, after these widows and Joe had passed away, Dad volunteered with Meals on Wheels. Once a week he would stop midway through his day, change from his work clothes into the identical but clean jeans and flannel shirt that he set aside for going to town, pick up the meals at the Nazarene Church, and deliver them to seniors at the local retirement home.

I rode along whenever I was back visiting my parents, and I was always struck by Dad’s change in demeanor as he made his rounds. To say my father was a man of few words would be an understatement. He and Joe could work together all day without saying more than a handful of sentences to each other — and two of those would be “Good morning” and “See you tomorrow.” But with the shut-ins he brought meals to, Dad was downright chatty. He would sit and make small talk with them about the weather, how the Spartans, Tigers, or Lions were faring, how they were feeling, and whether he could help them with anything or bring them something while he was there. As we put the meals in their refrigerator, he would check for and discreetly remove any food that had gone bad. In saying goodbye, he made a point of saying he looked forward to seeing them again soon.

Loyalty and reciprocity among neighbors

Dad had an expansive and enduring sense of connection to his many friends and neighbors in Mason. He reserved particular respect for community members who were good at their jobs, and he had strong views about who to turn to for help when something was beyond what he and Joe could manage. If there was tricky welding to do, you took it over to Cameron Glen’s shop. If the barn roof needed fixing, Harlan Whipple was the only man for it. Dick Fernburg, aka Fernie, had the magic touch with his backhoe. And when a sow got stuck in a troubled labor, you called Doc Patterson to come over and help deliver her litter.

A child of the depression, Dad never lost the sense of economic precarity that had marked his early years. He also grasped how the good jobs at the Oldsmobile and Fisher Body plants up in Lansing provided livelihoods for so many families in Mason. He was thus chagrined when, as a callow teenager, l purchased a thoroughly used but still racy French sports car. This was back in the early 1980s, when the Lansing factories were starting to lay off entire shifts of autoworkers.

I had saved up several hundred dollars from working on the farm for the purchase of this car, my first, and my heart was set on it. Dad wouldn’t tell me I couldn’t buy it. But he let me know that he thought this would be about the worst decision he had ever seen me make. He insisted it was too low-slung and thus not fit at all to drive in Michigan winters (reader, he would be proven right on this point many times). It would also be extremely hard to get parts for it (he was right here too).

But his main objection was that – as he explained to me with pointed exasperation in his final bid to talk me out of the purchase – “Your neighbors didn’t build that car!” That it was bright orange would make the fact that Pete Stid’s son was cavorting around town in a foreign-made vehicle all the more obvious and embarrassing. Two years later, when I sold the ill-fated Renault and bought a rusty Chevy pickup in its stead, he could not have been happier. His prodigal son had returned to the fold of the local economy.

The loyalty Dad extended to other members of the Mason community paid dividends as he got older. I noticed this the first autumn after Joe died. I was living and working in the Bay Area at the time and returned to Mason to help Dad out with the harvest for a week or so. I was also concerned about him being lonely, farming on his own after nearly fifty years of doing so with his brother by his side.

It soon became clear I did not need to worry about him being isolated. A steady stream of neighbors were coming by to keep Dad company. In the morning, as he and I went about checking belts and greasing zerks on the combine, they would regale us with familiar stories that never seemed to get old. When it was time to go out to the fields, some visitors would even climb up into the cab and ride along with Dad for a couple of rounds, talking or just sitting with him as he picked corn.

My job that week was trucking the corn he was harvesting to the grain elevator in town. Pretty much every trip, as I waited to unload, one or two farmers in line behind me would come up to talk. After joshing me about my decamping to California, they’d get around to asking how their friend Pete was holding up. These weather-beaten yet steadfast men, covered with dust from their own fields, had always known Pete and Joe as a team. Like me, they couldn’t quite get their heads around the fact that one Stid brother would now be carrying on farming without the other. They assured me that they too had been stopping by now and then to check on Dad, and they would keep it up in case he ever needed any help.

A final example of this reciprocity surfaced in the final months of Dad’s life. A neighbor that our family had known a bit, but not especially well, came by the week after she had retired. She said that now that she had more time on her hands, she would be glad to help on the days when we needed extra support, beyond what our family could provide, in caring for Dad. She then stood in our corner with an unflagging good nature until the end. It left our family amazed by her generosity. Early on, I shared our gratitude, all but asking her why she was doing this for us.

In response, she told me this story: Her father had been friends with Dad, the two of them having served together on the school board back in the 1970s. Later, her father had suffered an onslaught of health problems before he passed away in 2009. She recalled at one point being especially anxious as she drove her father home from a hospital stay. He had just been confined to a wheelchair, and she did not know how she would manage to get him up and over the steps that led into their house.

Upon arriving home, she discovered that while she had been away, Dad had come by and built a sturdy ramp for them. She was able to wheel her father right up that ramp and into their house. It was because of this unbidden act of generosity all those years ago, she said, that she was now sitting at the kitchen table in my parents’ farmhouse. And she would help care for Pete Stid as long as we needed her help.

Such are the goods and bonds that build up and circulate in a community’s civic culture when – year after year, decade after decade – its members associate with and look out for one another.

The quotation is from an oral history of my father’s life that I recorded with him in 2022. This oral history provides the source material for much of the discussion in this newsletter.